On an ordinary Wednesday in the fall of 2015, I arrived at LAX with a suitcase, a backpack, and an acceptance letter to attend The Chicago School of Professional Psychology. After a 10-hour flight from Oslo, I was ready to embark upon a new adventure in the City of Angels.

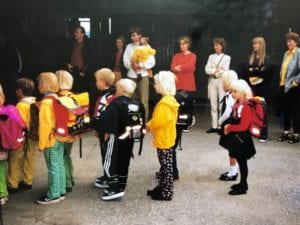

Growing up in Norway’s countryside, life was pretty simple. I went to school, played sports, volunteered in student organizations, hung out with friends, and started my first after school job at 14. I was a good student, received top grades and never rebelled.

Yuck, right? I’m only saying this to illustrate how there was no apparent reason to think there might be something “wrong” with me growing up.

TEFLON BRAIN

One incident has always stuck with me, however. It happened during a parent-teacher conference in 7th grade. My teacher in noting that my performance on our weekly quizzes did not match up to my usual standard, said: “Martine, it seems like you have a Teflon brain. I know that you know the material, but when the quiz is in front of you, all that information slides right off.”

Looking back, this has been a pretty consistent thing in my life. I do 95% of things really well. That remaining 5%, however, is an overwhelming sinkhole of frustration and stress. Intuitively, I know that I am capable of doing most things I set my mind to. Realistically, some of those things will still never happen. It can be minor stuff like misplacing things, scheduling appointments, or responding to an email. No matter how little the thing might be, it doesn’t change the exponential amount of energy I spend worrying about how I’m not getting it done.

A WAKE-UP CALL

During my second year at TCSPP, I was asked a few times if I had been assessed for ADHD. I guess that is a consequence of being around so many psychologists. When I moved in with my husband, there was no hiding anything anymore. A trained therapist, he quickly picked up on behaviors of mine that confirmed the suspicion I may not be entirely neurotypical.

I started reading more about ADHD and was stunned to see how many things applied to me. I was surprised to learn how differently ADHD can present in women and how often we are underdiagnosed. Instead women are often misdiagnosed with depression, bipolar disorder, anxiety, or other mood disorders. How messed up is that?

THE TIPPING POINT

Once I began my Ph.D. program, things quickly fell apart. All of a sudden, I couldn’t seem to do much besides work and sleep. Work has always been my excuse for procrastinating. For the past ten months, I have been seeing a fantastic therapist. During our very first session she posited that I have an inattentive form of ADHD. Receiving this diagnosis has changed everything, and nothing. I now understand why certain things are more difficult for me than others, and that it’s okay. I also know that I’m not inherently lazy or incapable of maintaining commitments. My therapist explained that I often procrastinate because I have to build up more adrenaline before engaging. Compared to neurotypical people, I essentially have to “jump-start” my nervous system to keep moving forward.

NOW WHAT

Receiving a diagnosis of ADHD at the age of 27, I could easily have felt bitter and resentful. Why didn’t anyone see me struggling sooner? Why didn’t I realize I was having a hard time? What would going to school have been like if I had known? Would I have remained more active? Would I have learned to keep better boundaries with people?

What I actually feel is grateful. Despite my diagnosis, I have had more success than I thought to dream of when I was younger. I’ve proven to myself that I have a tremendous capacity to work, study, and explore the world regardless of what barriers may be in my way. Moving forward, I get to enjoy living my life with more confidence and a deeper understanding of myself, and the knowledge to seek the tools, resources and support that works for me.

Behaviors that may indicate ADHD in girls and women:

- talking all the time, even when parents or teachers ask them to stop

- frequent crying, even from small disappointments

- constantly interrupting conversations

- trouble paying attention

- frequent daydreaming

- having a messy bedroom, desk, or backpack

- difficulty following multi-step directions and finishing assigned work

- sensitivity to perceived criticism

- compulsive overeating and chronic sleep deprivation

- fidgeting or doodling

- poor time management skills

- difficulty making and keeping friends, and understanding what’s socially appropriate

- often losing items, such as a phone or important papers

- experiencing strong emotions, which may prevent them from slowing down or thinking about what they say

Source: Children and Adults with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (CHADD)

Learn more about The Chicago School

The Chicago School provides you with an exceptional education rooted in innovation, service, and community. Enroll in one of our 30 academic programs today, or request more information by filling out the form below!