Toys have always been a reflection of society, from G.I. Joe launching in 1964 at the height of the Vietnam War, to Barbie representing the ideal (albeit problematic) woman with her perfect figure, blonde hair, blue eyes, and tendency toward homemaking. But toys aren’t all just fun and games: They have a real effect on children, and in conjunction, on society. This isn’t a new challenge, but it is one that has become more widely researched and considered in the past 20 years.

What kids see portrayed, and what they choose to play with, have real, long-lasting effects. This is why toymakers have long been an extension of social consciousness and, therefore, indicators of change.

Kristian Aloma, Ph.D., adjunct faculty member in the Behavioral Economics program at The Chicago School, explains what drives companies to evolve. “Most businesses are only inspired to change the status quo when the status quo is no longer relevant or is in some cases detrimental. This happens either after a dramatic, sudden change or after the incremental changes have built up for so long as to create a tipping point,” he says.

The companies that are charged with developing these toys have a lot of power, which is why their products continue to show clear examples of progress through the years. The stakes are high. In order to avoid becoming toys of the past, brands like Matchbox, Bratz, and Barbie have evolved with society on issues of gender, race, and able-bodiedness to continue their legacy.

The problem with playthings

From the ages of 2 to 5, children start to understand the concept of gender and in turn, what is expected of their gender. This doesn’t end after childhood, either. With women making up 28% of the labor field in STEM careers, it’s worth noting that a study on toy catalogs found that boys were four times as likely to be shown playing with cars and tools, and girls were twice as likely to be shown in kitchens or other domestic play.

Children are easily affected by marketing, and the toys they are presented with radically alter the way they see themselves now and in the future. A survey reported that more than 50% of respondents say gender stereotypes in the marketing of toys constrained their career choices, and 44% say this also harmed their personal relationships as adults.

“We’ve moved toward a more knowledge-based economy. We know better now, so businesses have to do better,” says Business Psychology faculty member, Maria Malayter, Ph.D.

Mattel Matchbox cars and Mercedes-Benz are doing something about this in their new ad campaign. “The goal: Inspire the next generation of female trailblazers.” This tagline leads the campaign targeted at girls. The advertisement ignores the narrative that boys play with cars, and girls play with dolls, showing a little girl with dolls on the table and a matchbox car zooming in her hand.

The Matchbox car is a replica of the Mercedes-Benz 220SE that Swedish female racing champion Ewy Rosqvist drove in her historic 1962 Argentinian Grand Prix race. She was mocked for even attempting the race, but she won every stage, set a speed record, and beat the previous record time by 3 hours.

Launching in 2020, Mattel and Mercedes-Benz are giving away thousands of these cars to young girls, hoping to show them another option for their toys and their lives.

But she doesn’t look like me

In addition to the gender boxes we force children into, what happens when there’s no doll that is the same color as they are? Most dolls have always been white, and any toys that had a different shade of skin were offered as an addition to the main toy or served as a “sidekick” or other nominal presence.

As young as the age of 3, kids start to recognize race and the way this affects how people are treated in the world. First studied in the 1940s and then replicated many times since, psychologists had African American children choose between white and black dolls. The children overwhelmingly chose the white dolls and described them with more positive traits.

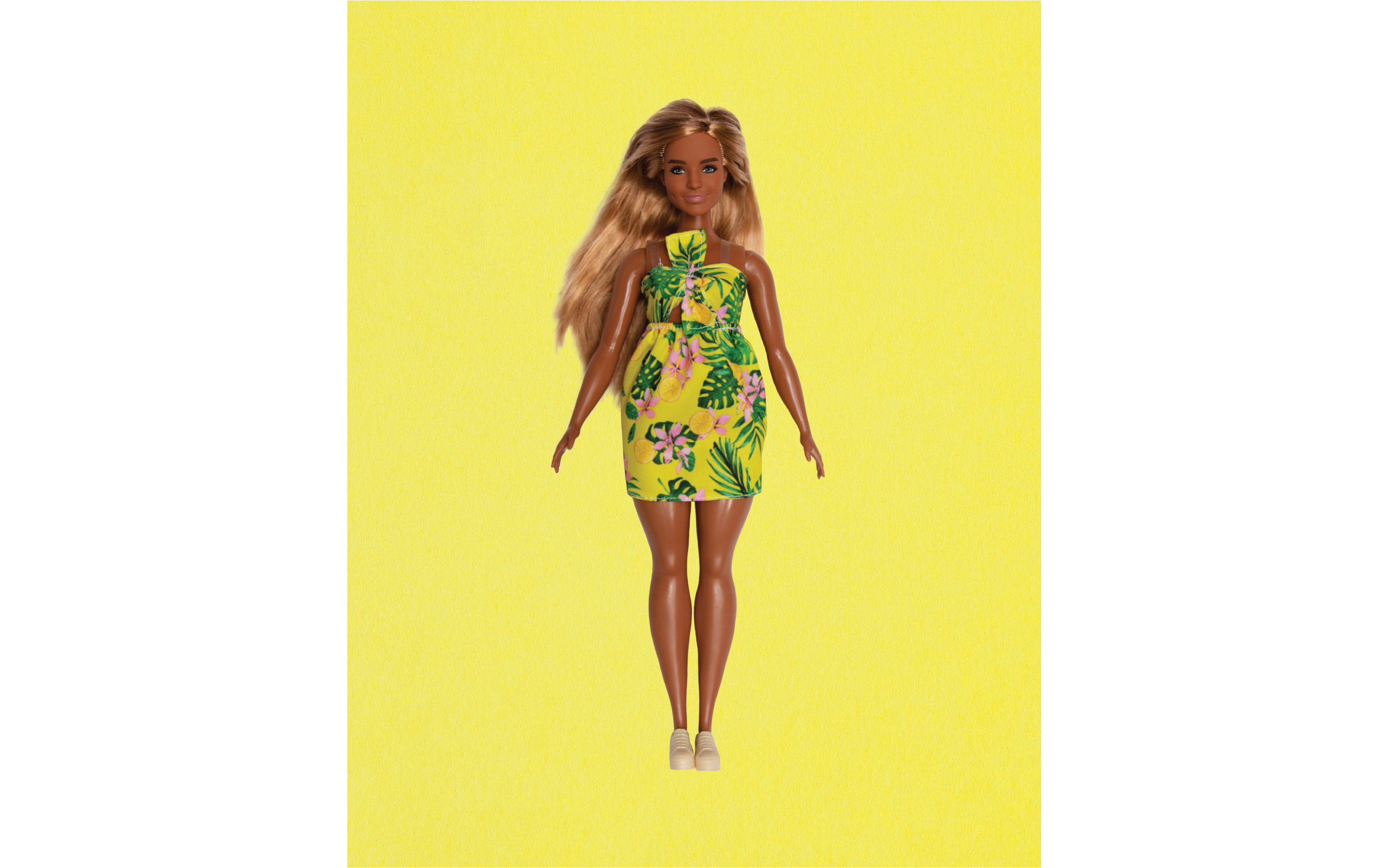

In 2001, Bratz unveiled dolls that looked like more than just a small percentage of society. Their starting lineup was made of four dolls, three of which were ethnic minorities: an African American doll named Sasha, a Latinx doll named Yasmin, an Asian doll named Jade, and a white doll named Chloe.

While the dolls were criticized for their fashion choices and makeup, they also gave children a new way to actually see a reflection of themselves in the toys they play with. No longer was white skin and blue eyes the only vision of beauty available—these girls were the stars of their own lives, too, not just an accessory.

Giving children a better way to feel comfortable in their own skin, the marketplace was ready to embrace the opportunity to showcase the diversity that makes up the world. In 2005, the Bratz line generated $800 million dollars in sales, nearly doubling Barbie’s $445 million that year.

When the business model is dominated by—and designed to benefit—a small portion of businesspeople, mostly white businessmen, there may be structures in place that aren’t recognized as problematic.

Perhaps one of the most recent outcries in our collective consciousness is the able-bodied privilege movement. Aptly pointing out that children with disabilities have always struggled with representation in toys, clothing, and movies, the movement is fighting the stigma around physical disabilities. Because of this historical lack of representation, children have looked for more ways to hide their disabilities and assimilate.

“When the business model is dominated by—and designed to benefit—a small portion of businesspeople, mostly white businessmen, there may be structures in place that aren’t recognized as problematic. They may not appear detrimental to any one group from afar, but with the right team, using a diverse set of lenses, these sorts of issues will become obvious and hopefully addressed,” Dr. Aloma explains.

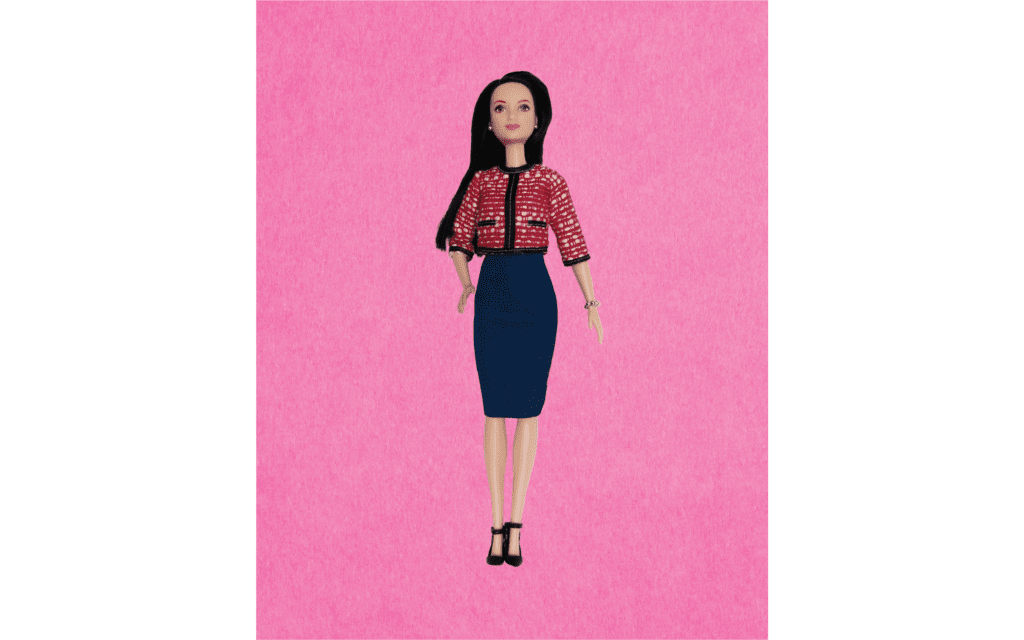

An example of this is Barbie’s recent release. As one out of 10 American girls between the ages of 3 and 10 own at least one Barbie doll, the purveyor of questionable beauty standards, the brand has responded to the need for inclusion with its new line featuring two dolls with permanent physical disabilities.

The new dolls are a part of Barbie’s 2019 Fashionistas line, which was developed with Jordan Reeves, a 13-year-old disability activist who was born without a left forearm. With more than one billion people in the world having a disability, the toy line has joined in making inclusion a priority.

One doll in the new lineup has a prosthetic limb, which can be removed. Rather than disguising disability, the new dolls are embracing it. Working with UCLA Children’s Hospital, Barbie designers also created a wheelchair and will offer a Dreamhouse with a compatible ramp.

Don’t throw out our toys

Dr. Malayter says that this need to survive and grow in the marketplace relies on a constant focus on learning. “The challenge today is everybody has to continue learning and growing as the population shifts,” she says. “There are a lot of moving parts, and in order to survive, the company has to know the demographic that they’re serving and how their life is changing along the way. Once they recognize that, they can create products that match what their needs are.”

Whether leading the charge or responding to the needs of their customers, toy companies shape children’s perspective while hopefully reinforcing a better tomorrow for everyone. The decisions to adjust their products to reflect a more diverse, inclusive population echo a desire to see that future as a successful company.

“It really is about how an organization is a learning culture,” Dr. Malayter says. “To remain successful, they have to always be taking one step forward to look at how the world is changing, thinking: how do we address this, what kind of changes do we need to make?”